SOLIDARITY ECONOMICS

written and illustrated by Dionne Co

Solidarity Economics is a set of ideas and practices about alternative ways of engaging in the economy. Solidarity Economics is a "movement of movements" continually seeking connections and possibilities while holding on to the transformative commitment of shared values.

Solidarity Economics operates on this core belief: that people are deeply creative and capable of developing their own solutions to economic problems, that these solutions will look different in different places and contexts, and that all these can be connected with each other in mutually-supportive ways.

Solidarity Economics does not come from a single political-economic idea or theorist. Instead, ideas about Solidarity Economics evolve through a collective process, crafted plurally through participatory economic forms and relationships built over time. In Solidarity Economics, practice shapes theory.

The practical dimension of Solidarity Economics develops through the diverse, creative ways that people engage economically without submitting to the mainstream market system, ruled by the logic of individualism and profit accumulation.

Examples of these practices include:

worker cooperatives

fair trade initiatives

alternative currencies

community-run centers

resource libraries

community development credit unions

community gardens

open source free software initiatives

gift economies

ethical purchasing

democratic nonprofits

forms of household production, self-employment and self-provisioning.

The Concept of Solidarity Economics: Values and Economic Spheres

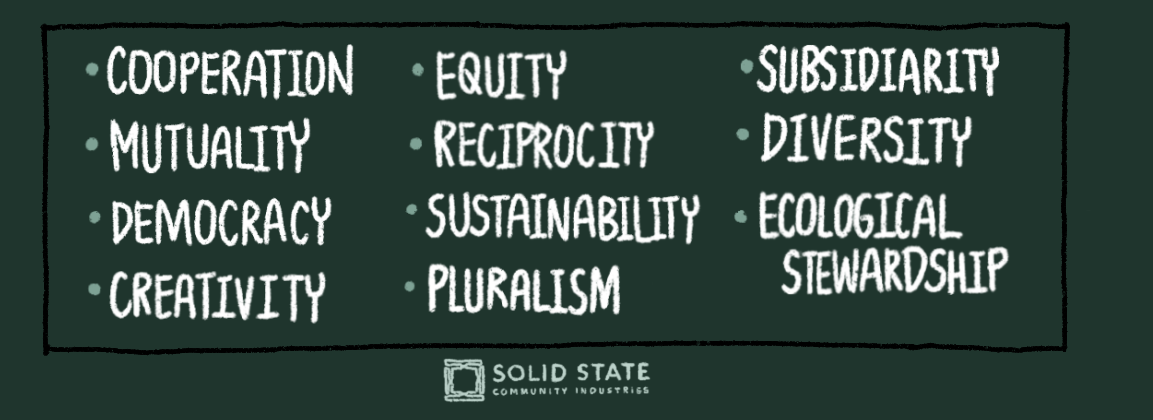

Despite the plurality and diversity of economic initiatives within the Solidarity Economy, what binds these movements together are shared values. A recognition of interdependency is at the heart of this economy: that our lives and fates, although coloured by differing levels of power and privilege, are ultimately bound together.

Solidarity is enacted when we realize our connectedness and actively work to steward our relationships with each other, not only with people but with animals and the earth too. Common values articulated within the solidarity economy include cooperation, mutuality and reciprocity, with more examples illustrated.

Solidarity Economics views the economy as a social institution, not as a separate sphere of life. This stands in contrast against mainstream capitalism where work is separated from life – consider how common understandings of ‘work’ mean that we are made to suppress our autonomy, defer to our superiors, wear a dress code, put on a professional mask, deny our bodily needs, and numb ourselves from how we feel.

Within the Solidarity Economy, work is embodied and submerged within social relationships. For example, at Solid State, we form cohorts with people of our choosing. We do not serve bosses, nor do we want to become bosses. We plan and scheme, talk about our lives and our problems while devising ways of making money and honouring our creative spirits. We eat together. We become friends.

Capitalist Economics versus Solidarity Economics

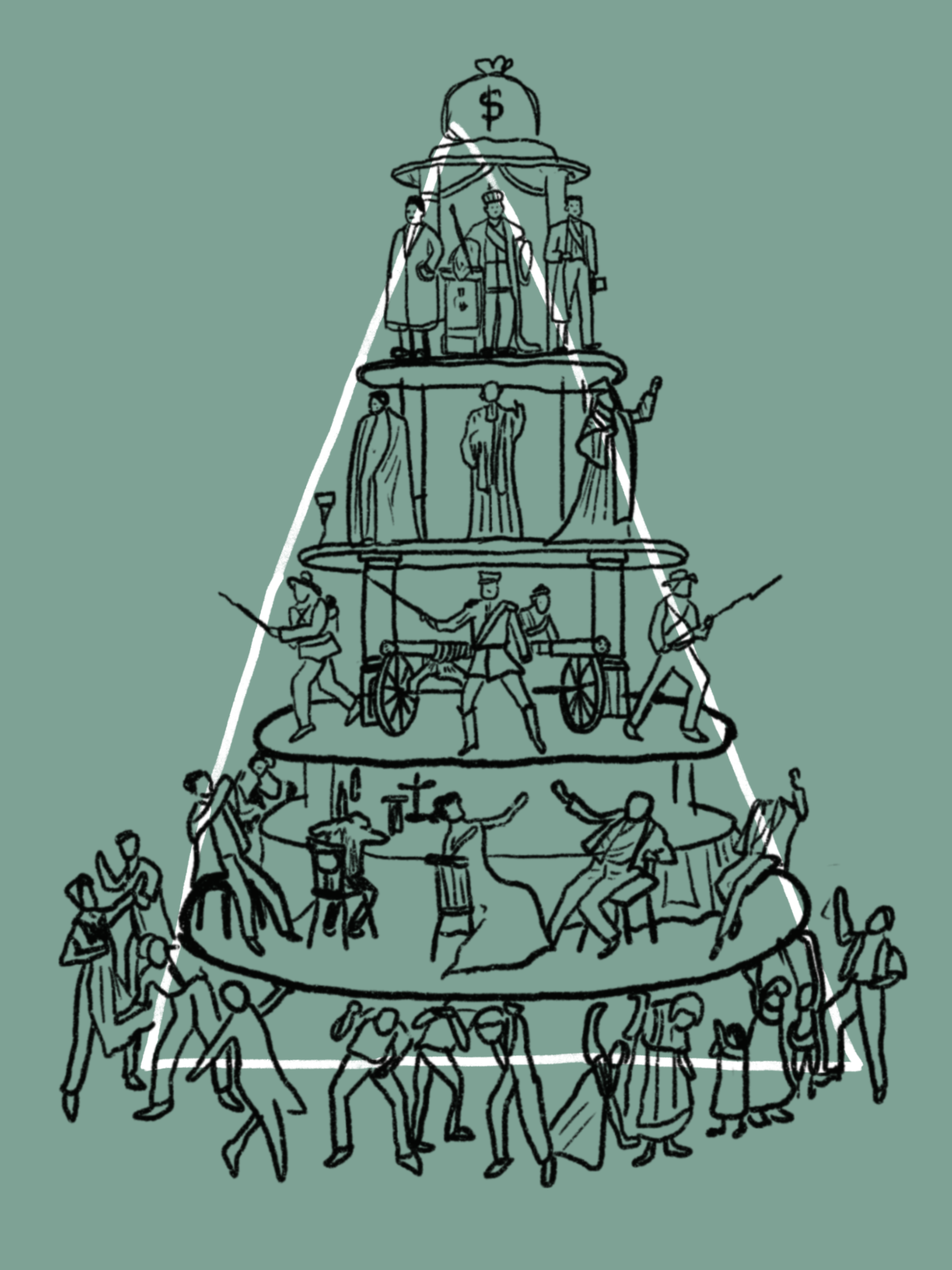

If capitalist economics is a pyramid, then we can imagine Solidarity Economics taking the shape of a constellation.

In large part, Solidarity Economics emerged as a movement and practical response to the failures of mainstream capitalism: a system that places the profit and well-being of the few above everyone else, leading to widespread inequality and suffering for many people in all parts of the world.

Historians often cite the 1980s as the era when Solidarity Economics emerged in its contemporary form, beginning with the cooperativismo movements in Chile and Colombia. By the mid-1990s, economia solidaria developed into a broader social movement involving networks of economic activity not only in Chile and Colombia, but also Brazil, Canada, France, Spain, Peru, Argentina, Mexico, Senegal, the Philippines – eventually culminating in the first internationally organized group, the Intercontinental Network for the Promotion of the Social Solidarity Economy (Red Intercontinental de Promoción de la Economía Social Solidaria, or RIPESS).

Having said that, Solidarity Economics is not new, nor did it begin at one fixed point in time. Indigenous nations and groups have engaged in these kinds of economies since time immemorial. Feminist economists have also documented and acknowledged the different ways in which women have long sinced practised solidarity economic work through domestic labour and care work at home.

Presented is a table that compares some structural differences between Capitalist Economics from Solidarity Economics.

“We are building in the midst of contradictions, in the cracks of capitalism, a new type of society and economy.*” Though capitalism dominates, there are spaces of hope and other possibilities in between. A better world is not only possible, it is already here.

*Guerra, Pablo. 2004. "Econom.a de la solidaridad: consolidaci.n de un concepto a veinte a.os de sus primeras elaboraciones." Revista OIKOS . Universidad Cat.lica Cardenal Ra.l Silva Henr.quez, Santiago de Chile.